An Interview With Mike Netzer - Continuity Studios and A Spiritual Awakening

/Written by Bryan Stroud

Mike Netzer, holding a Batman commission.

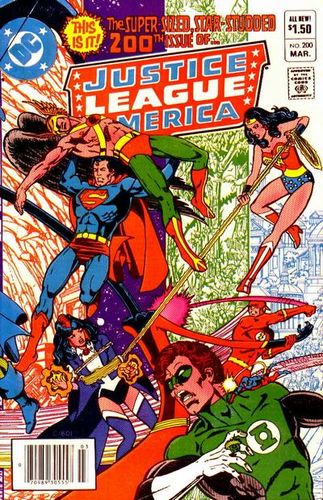

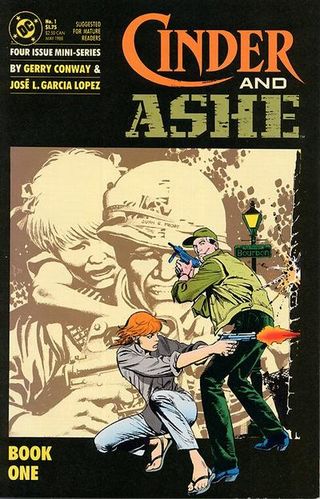

Michael Netzer (born Michael Nasser on October 9, 1955) is an American-Israeli artist best known for his comic book work for DC Comics and Marvel Comics in the 1970s. Mr. Netzer joined Continuity Studios in 1973, where he created art for both Marvel and DC as a member of the Crusty Bunkers. In the late seventies, Mike left Continuity in a move that eventually saw him relocated to Isreal. In the early 1990’s, Netzer would open litigation against Neal Adams claiming ownership of the character Ms. Mystic - a claim that he maintains to this day.

This particular installment of the Crusty Bunker series was especially fascinating. Not only did Michael have a lot to share, but it was my first time reaching out internationally, as he was (perhaps still is) in Israel at the time. Michael was generous with his time and remembrances and boy, did he have some adventures, as you'll soon see.

This interview originally took place over the phone on September 25, 2010.

Adventures on the Planet of the Apes (1975) #7, cover penciled by Mike Nasser & inked by Klaus Janson.

Bryan Stroud: There seem to have been a few different paths to Continuity. What was yours?

Michael Netzer: I was invited by Neal [Adams]. I was about 18 years old at the time. I was in Detroit at a big comic book convention there put together by Greg Theakston and it was called the Detroit Triple Fan Fair. Greg was someone that I knew in high school and he was encouraging me to try and break into the business. He saw something. He saw my enthusiasm for it and he sort of helped push me into it. He had this convention and he invited Neal Adams among other guests, like William Shatner and some of the Star Trek people. Jim Steranko was there and as I remember Vaughn Bode was invited. He (Greg) asked me to be in charge of Neal and to pick him up at the airport and to make sure that he had everything he needs and so on. He did that purposely because he knew how much I was attracted to Neal’s art and what an influence it was becoming on my own work.

So, when Neal came I went to pick him up at the airport. It was a pretty odd situation because instead of the sort of vehicle you might expect, I went to pick him up in my 1964 Mustang. This was in 1973 and it was like going to a convention in a car that looked like it had been through World War II or something. I bought it for $100.00. It featured a convertible top with a hole in it. As it turns out, on this September day that I was picking him up it began to rain a little bit. So, we’re driving and water is starting to get into the back seat and I’m sure Neal was wondering what he’d gotten himself into.

So, this was my first big comic book convention. I may have been to one smaller one in Detroit, but this was my first direct contact with comics fandom and it was a very big deal for me. Neal had seemed to particularly take interest in things personally. He hadn’t yet seen my work, but he seemed good with this kid who had come to pick him up who was, at the time, very much the quiet type. Very withdrawn. I didn’t say much and didn’t appear to have an outward involvement in very much. But I was a good listener, and Neal was a good talker. (Chuckle.)

We got to the convention and there seemed to be a good chemistry between us. As things went along and he started seeing my work he took an interest in it. He invited me to come to New York and work at Continuity if I ever had the chance. I have to say that my work at the time didn’t look much like it was influenced by Neal at all. Mostly what I had to show were drawings I’d done in a life drawing class that I did in college. Interestingly enough it had a look altogether different from the comic book work that I do. It had more of a drawing look, more like an illustration, but at that period in time I was drawing more for drawing as opposed to comic book art. I think maybe that was what interested him more than anything. He knew I was a big fan of his work and was enamored of it before he came to Detroit through Greg Theakston. So, at the end of that convention I got the invitation, which was a very big deal for me.

Star Trek (1980) #7, cover by Mike Nasser.

As an aside I’ll tell you at that convention I had done an exhibit of some art that was 6 pieces of the Star Trek crew and at the end of the con Neal was there when Greg told me that one of the drawings was missing from the exhibit. They thought that somebody had taken it. They were apologetic about it, but it seemed to me that it was kind of cool that someone liked my drawing enough to take it from there. I say that because recently someone contacted me from Detroit and said they’re putting on a convention in remembrance of those days of comic fandom from the 60’s and 70’s and they’re calling it the Detroit Fan Fair, not the Detroit Triple Fan Fair. But the guy that contacted me told me that several years ago he had bought a box of old comic books and inside of it was a few drawings and one of them was this drawing of Captain Kirk and that my name was signed to it and he asked me what I could tell him about that and how it had come about. I told him the story that this was the drawing that was taken from the exhibit and he basically invited me to this convention that’s coming up in October where he’s going to return it to me. Along with that we’ll be publishing a sketchbook of the last few years and the story of that drawing will be in the front of the book.

It’s an interesting theory that a big circle is being closed right now from that convention that was exactly 35 years ago to now.

Stroud: Oh, what a magnificent story.

Netzer: Arvell Jones, another of the Detroit area people along with Keith Pollard broke into the business in the 1970’s and they were together at the time. Keith Pollard worked for Marvel back then. They were driving up to New York to try and break into the business. This would have been late October 1975. The asked me if I wanted to come along for the ride and see if I could get in, too. Of course, I had the invitation to go to Continuity, so that was a good step. I had something to rely on, so I took my meager funds, maybe $100.00, knowing I at least had a place to stay for a short time.

So, I took that ride with them and went to Continuity the next day. Neal told me, “Look, I don’t have much work right here, but here’s the phone book and a list of contacts including DC and Marvel. Call them up and see if you can get an appointment to show them your work.” I did just that and had a couple of appointments lined up. One was with Jack C. Harris at DC Comics, who promptly gave me a script for a story in Kamandi. That’s how my career started. I also did a little bit of commercial work with Neal, penciling story boards and sometimes inking backgrounds. So that’s how it started, in late 1975.

Chamber of Chills (1972) #24, cover penciled by Al Milgrom & inked by Mike Nasser.

Stroud: So, you kind of got spring boarded from Continuity into your comic career.

Netzer: Exactly. Now I’ll try to give you my perception of what Continuity was at the time. Naturally, Neal’s personality was the dominant one. To me it was a whole new world. I’d just come from a limited home/school life and was thrust into New York City and the hopper of the comic book industry. So, there was a feeling of being overwhelmed and also taking into consideration my age at the time, barely 20, and was still a very withdrawn and introverted man. Aside from wanting to be a comic book artist, and being thrust into this situation, I just tried to make the best of it. My own personality was fairly optimistic. I had the feeling inside that I was living at a very important time and that some very big things were awaiting us. I’m speaking generally as a civilization. There was something in the air. Something important about being there at this particular time.

Now most of the people in Continuity were young people who were looking to break into the business. Maybe they’d got their first independent script to draw. There were a few artists like that at least. I basically became attached to some of the artists like a guy named Mark Rice, a guy named John Fuller. Joe Rubinstein was one of those. They’d not really done any independent work. Along with that there were a lot of established professionals there like Cary Bates, Larry Hama, Howard Chaykin, Walter Simonson. A lot of them were beginning to make a presence for themselves in the industry. Continuity was a hub in every sense of the word.

When I landed in New York it was basically in the throes of helping out Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. The day I landed I was in the front room all the time and Siegel and Shuster were visiting at Continuity and Neal was giving them some details on how to move forward and convince DC Comics to give them a little compensation for the creation of Superman. That was a pretty big event and this was when I began to understand the rather peculiar personality which was Neal and that he was very involved in the industry and very involved in making things better for others in the industry.

This was a little bit unique because most other artists seemed to be more than anything else worried or concerned with advancing their own career. Very few were showing the kind of extending of themselves towards this sort of activity. So right away I became a part of a very good spirit that was in the studio, which kind of had an overall look at the industry and it seemed that there was a feeling that from Continuity, there was a very big influence over what was going on in the comic book industry.

Wonder Woman (1942) #231, cover penciled by Mike Nasser & inked by Vince Colletta.

Stroud: I think your describing it as a hub seems very appropriate, at least from what I’ve heard from others who were involved there. It has been described as a middle ground between the big two publishers.

Netzer: There is certainly that. There were artists and writers and editors from both companies who felt at home there. And people who worked at Continuity were working for both companies. It was a middle ground and it was also a place where the people who were involved in it seemed to have some influence over what was going on in the industry. Meaning that Cary Bates was writing Superman and having the regular writer of Superman at Continuity meant that everything that was going on with Superman and everything that was going on at DC Comics at the time was known and by knowing that it kind of helped us to do our jobs a little better and maybe people who weren’t exposed to this kind of environment wouldn’t be aware of it.

Now I just want to add one more aspect to this. At the time, on that first day, there was something very interesting that happened. A big poster on the wall next to Neal’s desk in the front room was a map of the Earth. I believe it was a map of the ocean floor. It was a picture of the ocean floor without the water. It was a very interesting picture that I’d never seen before. Somehow, right away, I was pulled into this discussion and I remember Neal looking at it and he said, “You know that geologists are saying that the continents have moved around and they used to be together, but they’ve spread apart. Now look at this map. Does it look to you like the continents can move around on the ocean floor the way they show it?” I said, “What are you talking about?” It was a little bit of overload. I wasn’t familiar with the theory. I mean I’d heard of Pangea, but never really got into the details and I found myself going out and reading and researching so I’d have an idea what they were talking about. At that time Neal hadn’t yet started talking about the planet may be growing and that the continents spread out because of it. All this about the organic matter coming from inside. But he was trying to pick peoples minds and say that there was a problem with this theory. The idea that the continents were moving around just didn’t make sense to him. This would have been around 1975, so it was the period when Neal was starting to formulate his resistance to a very popular new scientific theory and he was looking around to maybe see what people thought of it. A lot of people came in and whenever he found people to be of interest, he would open up that discussion in the front room.

Ghosts (1971) #97 pg.4, art by Mike Nasser.

It’s interesting that most of the people there didn’t have anything to say about it and Neal was going to go up against the scientific community and who would know more? People just didn’t seem to know where he was heading with that, but you could see back in 1975 the beginning of this idea which for Neal has become a very important part of his work. You could see the seeds to it right there.

So, to me I felt that I’d pretty much found myself in the middle of a very serious and pertinent kind of place. And here I was in the midst of the place and person whose artwork had pulled me into the comic book world. This man was proving to be a lot more than just a comic book artist with great ability, but also someone working on a humanitarian level and with an overall view of the world and he seemed to care a little more and be involved in it. He felt he could be an influence on any aspect of it. A conversation with him would move from anything to politics, to social issues, to what was going on in the comic book industry. He was someone whose view was more than just worrying about advancing his own career. Rather he was someone who would be engaged in many aspects of the world we were living in. To me that was very important. I had been instinctively pretty much the same way.

So as time went on, this interesting bond was forming between us. I would say that it may not be like a lot of people that shared that engagement that Neal had in the studio. I like to think I lent my support to that right from the beginning and it created a very strong bond between us.

Another interesting aspect to this is that I saw a lot of artists come in to show their work and some of them were not so bad. Let’s say that they were…I wouldn’t want to grade anyone, but I would say that it seemed like almost regardless of what identity these people were bringing in, Neal’s criticism of their work was evidently harsh. It took me a long time to understand how or why he would do it. What was interesting was that with me, particularly, is that I never faced that criticism from him. He seemed to treat me with kid gloves and it was just the opposite when some of these kids would come in to show their work. There were times when he would bring them back to my table and he would actually pull out one of the drawings that I did. I remember a splash page from the Deadly Hands of Kung Fu that I did during that early period and spent a lot of time on and he would bring them back and he would say, “See that? This is how good you have to draw to get into the business.” So he would use me as an example to show young artists the extent of the work that they had to do.

Megalith (1989) #7, cover penciled by Mike Nasser & inked by Rudy Nebres.

So, what I would take from all this is that from my situation, personally, my work seemed to be a little different than what most other young artists were facing at Continuity. I think it can be attributed a lot to a very positive outlook of mine toward the future in this new life that I was beginning in New York.

Stroud: That’s quite a remarkable chain of events that you’ve described.

Netzer: It is pretty remarkable. Again, I think it was something in the chemistry between us. I have to say that I think there was an aspect to me that contributed to the whole thing. I’d basically been raised in Lebanon. I was born in Lebanon, but I came to America and by the time I came to America, between the ages of 12 and 19, those critical school ages, I was extremely withdrawn. I wasn’t really engaged in American culture. I had to do some catching up. There was some culture shock to deal with and it felt like instead of starting my life at 5 years old, where you typically start going to school and so on, I started at 12, so I had something like 7 years missing. I felt like I was behind everybody else.

I found myself a little bit disengaged from the kind of life that most kids my age were living. So, by the time I got to New York and began working, I was missing basically a lot of the culture that my colleagues had. I hadn’t grown up in America throughout that whole period. There was Greg and others and these were the people who were at the forefront of media and culture in America. Comic book artists and writers were just very interested in what was going on in film and in books and science fiction and everything. So the conversation between them would inevitably be around certain things. People would talk about Humphrey Bogart and Casablanca and Citizen Kane and James Cagney and things in the culture that left a very big impression on them from the world of film and television and actors and books and so forth and I just didn’t have any of that.

It was like an immediate overexposure to the world. When everyone else seemed to be involved in these conversations it would bring out the impact of these things in comic book stories and so on and I had very little of that. I found myself always on the outside and learning and absorbing as much as I could. I had a lot of catching up to do. I was very interested in knowing what everybody was talking about. I think that contributed to something that was distinguishing me from everybody. Maybe that needed someone who was like a little kid in an environment of a lot of grownups who needed this kind of perception. I think Neal instinctively felt in this situation that he took it upon himself to be that guy, to be the one that would take care of me as I was taking these steps of getting acquainted with everything.

Amazing Spider-Man (1963) #207, cover penciled by Mike Nasser & inked by Al Milgrom.

I think that also contributed to the bond and contributed to the difference in this particular relationship that we had, relative to the kind of relationship he had with other artists.

I would also say that I shared and supported his larger outlook on the world. That being engaged and using the position you have, or using your time in this journey through life to do what you can to contribute to making your environment a little better. It’s to have an overall large outlook on things so that you can be engaged in almost anything you need to see where you can contribute in a positive way. This was a little bit unique and I think that Neal was pretty much wanting to do that. It was the crux of what he was doing in this life and I think he still feels that way, and you can see it even today in everything that he does.

It wasn’t such a shared thing…it wasn’t clear to everybody in the studio and in that environment shared that feeling with him and sometimes it was even said that it was just an eccentricity of Neal’s that he was that way.

With most people, you have your career and you have your life and you have your own things to take care of and that’s enough of a chunk to deal with. A lot of people thought, “Well, that’s all there is. I can’t change the world.” Certainly, we all run into this situation where we get cynical. “So, what, you think you can change the world? The political situation, the economic situation?” But then some actively try to see where the weaknesses are in what humanity is going through and try to improve them in some way. And here I was in the situation I was brought into, drafted into this thing with the kind of optimism that you have the ability and yes, you can do that. To have someone like Neal around just pulled me right into that inner world of his. And there was a big feeling, at least for me, and I’m sure it was for him, that this bond that was developing between us was something that is going to lead to some kind of an ability to be some kind of a contributing factor. The steps that we were making for ourselves.

Neal has a big world within him. It’s really rare that he expresses the depths of that world that is within him, so he has his own way of concentrating on things that open up certain avenues, especially the way he talks about his contributions. How the comic book industry was shaping up. To me it was very clear. When Neal and I would talk about the idea that comics…and this was back in the 1970’s. You have to remember that comics were going through a very difficult time. They had been through the 50’s already and there was some new energy coming into the business now with artists like Wrightson and Kaluta and Jones. Having gone through the Green Lantern/Green Arrow run. The feeling that comics were now somehow becoming pertinent. The sales of comics was still very much questionable at that time. There wasn’t a lot of optimism in the industry for where the industry at large was heading.

Batman / Green Arrow: Poison Tomorrow (1992) 1, cover painted by Mike Netzer.

As a matter of fact, I say this all the time. A lot of creators from that time would be very enthused about what was going on in comics at that time. They might not be getting a piece of it. They might not have a lot of work because there was so much talent and a lot of the creators from that time found themselves jobless and outside the industry and they had to look for their work somewhere else. Still, most of the creators I’m in touch with still cannot deny that at the time, in the 70’s, they never dreamed that comics would have the influence they do today in our culture. This is a very important thing because we seemed to have, at that time, during that early period, this new spirit that was new and that Neal had injected into the industry through Continuity, being a hub where a lot of creators were coming in.

This led to a serious effort to get the artists and writers together to create a comic book creator’s guild. Something that Arnold Drake had tried in the 60’s after working at DC, and it didn’t work. We found the same thing. I remember Neal asking me to try to write some kind of beginning of a charter of why we needed to do this. There was a lot of talk with a lot of artists. It was amazing the resistance we had from the actual artists and writers themselves. It was amazing how many established creators were reluctant to put their name onto this piece and to support the idea that we present a unified stance to the publishers. People were just afraid for their jobs. They were afraid that DC and Marvel would stop giving them work and so we had to work very hard to get the things that we did on it.

Tomb of Darkness (1974) #22, cover penciled by Mike Nasser & inked by Pablo Marcos.

In the end it turned out that it really wasn’t enough to put together a guild. But the effort was made. Steps were taken and some things were written and names were signed on. What this indicated was a general feeling that the industry was not up to speed with the vision that seemed to be coming out of Continuity. That made for an interesting struggle and dichotomy for a particular problem that we faced. Because if we could not do this, then it seemed that the industry would continue to develop in such a way that the state of the creators would remain as that of an underdog because we didn’t have the ability to put forth a unified stand in order to be rewarded fairly for the work and the contribution we were making to the industry.

Now just to put that a little bit in perspective, I think it’s really important to understand one of the reasons we felt comic book creators really should be at the top of the pyramid. The main reason being, most everything that the comic book industry was basically came from creators. There isn’t a character, there isn’t a property you could say that a publisher created. At best you could say, “Well, look at Stan Lee. He was the publisher and look what he did.” Stan wasn’t a publisher. Stan was a writer/editor. Basically, everything he did, he did under the auspices of him being a comic book creator, not as a comic book publisher. Stan was editor in chief, but without Jack Kirby it would be very questionable whether Stan could come in and create the surge that Marvel went through in the early 60’s with the characters and stories and properties.

This is the thing that came from comic book creators. The people who owned Timely, which became Marvel, were not the ones who created these properties.

Stroud: Not at all.

Netzer: The same with DC. You could look at everything that DC has developed over the years and it all came from the creators. The creators were the source of everything that the comic book industry has become. And when you look historically at what the comic book industry has become and where it’s going, it is the leading source for entertainment properties in the world today. I’m not just talking about the super heroes, I’m talking about everything. The breadth of the comic book industry, the independents and everything that has come from the periphery of the indies world. It’s going into film. This is all the work of comic book creators. Without them, none of this could be.

The Huntress (1994) #1, cover by Mike Netzer.

And yet, even to this day, I finished a job for Dynamite Entertainment and I’m still getting a contract that says, “Work for Hire” for doing these eight pages for Dynamite. I know that the page rate I get from Dynamite puts me back to a time from 20, 25 years ago. It’s like half the page rate I was getting from DC comics in the 90’s when I returned to do a few Batman stories. That’s the story, that’s the situation comic book creators are living in. A situation where the publisher is taking these properties, making millions and billions of dollars on them, from properties that no one there had created themselves. It all came from the creative community and they find themselves fighting for every bit of right that they get. For every little morsel of bread that they get. Droppings that they get from the table of the publishers.

It’s kind of like there is a serious, serious injustice going on and being perpetuated in the comic book industry that comic book creators find themselves powerless to change. Even to this day. That’s kind of an interesting dichotomy, because you could say, “Well, back in the 70’s, that was also the same situation,” but back then nobody dreamed that the industry would flourish to what it’s become today.

On the other hand, we have a very interesting situation where the comic book publishers continue to this very day to keep presenting the same situation that the comics aren’t really making enough money. “We can’t compensate you any more than we do for your work.” I don’t know. Someone is cooking the books, it seems, or someone is telling these weird kinds of stories, because comic book companies are making a lot of money. If there’s a reason that comic books are not making a lot of money, then somebody has to look at whether the publishers are happy with the situation. I mean, come on. Why would the publishers continue making this product that isn’t making any money? Well we all know that they’re making money. They’re making it from peripheral projects. It seems almost like it’s in their best interest, the publishers, that the comic books don’t sell a lot and they make a lot of movies and a lot of products that make a lot of money and this is very much in the interest of the publishers because they can keep the creators at bay and say, “Well, look, the comics aren’t making money, so we’re not in a situation to compensate you for the amount of work and contribution that you’re making for the industry.” This way they can get off the hook and keep the creators at bay and they will have to settle for a situation where they give away their intellectual property for characters that they create or they never get a proportionally fair reimbursement for the work that they’re doing.

DC Special Series (1977) #1, Batman-Kobra penciled by Mike Nasser & inked by Joe Rubinstein.

Because the industry just isn’t making money. As far as the publishers are concerned it’s a wonderful situation. If the publisher tells you that the comics aren’t making any money, it seems to me the publishers haven’t bought anything to help the comic books themselves make any money because they don’t need to. And it serves their interests because the creators can’t get for themselves what they need. It’s a terrible, vicious circle. I think that we began seeing that in the 70’s. I think we saw the germination of that, which has continued even to this day. The industry has grown and grown and grown and creators are still at the very bottom end of this thing although they are the major contributors to this industry.

Stroud: The sales figures would seem to bear out their position. I think they peaked in the post World War II timeframe, so pointing to that it would be easy to say, “Sorry, guys, but we’re just not selling enough copies.”

Netzer: Exactly. They might come and show you the numbers and, “Look at the numbers, look at the sales. We’re only selling 40,000 copies of Superman.” Back in the 70’s they were selling a couple hundred thousand of Superman and Batman. Today the numbers are like half or a third of what they were selling back then. And nobody can argue with that, you know? The comic book industry is like on the ropes. Well, it’s not true. They lie. That’s a really big distortion of reality. The publishers are making a lot of money from the comics. They might not be making it from the comic books themselves, but without the comic books they would not have these properties to make films from and to do all these other things and produce the merchandise that they are producing.

Stroud: The licensing. I suspect it’s not accident they keep getting sold to larger conglomerates like Marvel to Disney for example.

Netzer: Exactly. They’re not stupid. Now of course throughout all this we saw some very nice things in the 80’s. Certainly, the idea of the Image guys coming together and the opening up of the industry on the one hand was a very good thing. It seems to me like the distribution is a factor. I look at the distribution and I can’t believe that the people who are running the industry are so stupid that they think this is a good distribution system that we have today.

Marvel Two-In-One (1974) #70 pg.2, penciled by Mike Nasser & inked by Gene Day.

Marvel Two-In-One (1974) #70 pg.3, penciled by Mike Nasser & inked by Gene Day.

Marvel Tales (1964) #100 pg.26, penciled by Mike Nasser & inked by Terry Austin.

If you have a property that has any potential, any shot at being successful, the distribution system is working against that right from the beginning. The idea of direct sales and selling your books ahead of time before you see the project, and basically that the success or failure of the book has already been predetermined before the book is published? By the amount of the advance sales at the store where it’s being sold? You want to tell me that this is the best way to sell a product? Wouldn’t it be better to put it out there, without selling it in advance, without putting it into a situation where people have to pre-sell the amount of books they’re going to sell? How do they know? Do they know only by the PR the company is putting out? That means the company determines ahead of time what comics are going to make it by the amount of PR, the campaign they give to every product? Regardless of whether it’s a good product or not, this is a very good situation for the publisher because they can say, “Well, you know, we’re going to do Infinite Crisis and Endless Crisis and one Crisis after another…”

Armageddon: Inferno (1992) #1, cover by Mike Netzer.

Stroud: (Laughter.)

Netzer: “Crossovers. And these are the ones that we’re going to push. And they will sell because we pushed them ahead of time, and whether this product is good or bad and whether the readers wanted it or not, we don’t care. In fact, we’re determining the sale of this product from the beginning.” And the readership really has nothing to do with it because the readers don’t buy the book. It doesn’t matter. The company has made their money. And they really don’t care if the stores are able to sell them or not. It doesn’t matter. No one can do anything about it because of the distribution system that exists. This is the awful situation. There is no other product being sold that way in the world!

Stroud: You’re absolutely correct.

Netzer: It’s a very strange situation.

Stroud: It doesn’t seem to reflect the market in any realistic way.

Netzer: No. The market is forced to like or not like this product that is being spoon fed to it. They are forced to like or not like it based on the position on the scale that the publisher is giving this product. Again, it seems to me that if I were the publisher at DC or Marvel and I was looking out for the interest of the publisher, and was trying to keep the creative community at bay, then this would be the best way to do it. I would support the system because this way I could control a system where we can control the sales and we can make it look like these properties are not selling very well, not selling enough. To decline, over the years, and they continue to decline, and we can make all of our money on films and other merchandising and this way we can maintain full control of the properties and acquire these intellectual properties to ourselves without the creators having any leg to stand on to get the rights that they duly deserve as creators.

Now I didn’t really want to get into this whole negative thing with the industry situation. I do want to get back to Continuity. That is what this is about. (Mutual laughter.)

Megalith (1989) #6, cover penciled by Mike Nasser & inked by Neal Adams.

Stroud: Well, I appreciate the insight just the same. How many years did you spend at Continuity?

Netzer: The peak of my career was basically two years between 1975 and 1977. After 1977, those two years were the learning curve for me. What is very interesting is I got to New York and in a way that one aspect of my art, which is drawing stuff, that ability to draw seemed to go on the back burner and I became more of a comic book artist. I wasn’t drawing drawings, I was drawing comic books. The 70’s, working at Continuity, and the two years of doing art took a front seat and I worked so much that it was a little scary at times because it wasn’t just drawing. Our handwriting was the same (mine and Neal’s). My natural handwriting was pretty much like his and everything seemed like this synergy of things at Continuity with Neal. Those were those two years. It was a big learning curve, learning to do what Neal does.

I wasn’t looking to do it better than he does. I was just trying to do things the best that I could. I didn’t think it could be done better than he does. I wasn’t aware of where I would be taking my art at the time. I just pretty much put my mind to concentrating on that learning curve of absorbing everything I could in those two years. The cultural world that was around me, at Continuity, whether it was the actual craftsmanship of drawing, or whatever. I think during this two-year period you could see a marked improvement in everything I did. There seemed to be an attitude there of, “Keep an eye on what this guy is doing, because it looks like he’s getting better really fast.” It took something like a year and some time in the later part of ’76, maybe the first book I did which was a Challengers #82, the second Challengers where Neal got the bundle that came in from DC Comics to Continuity and he flipped through the bundle and he looked at that Challengers that I had done and he saw me working on it and he looks through it and comes back out and he’s holding the book in his hand and he was really enthused about it.

To me it seemed to be a turning point. It was also a bit of a turning point on the Batman/Kobra that I did. The turning point was like I’d gone from the point of being like someone who was looking for his way as an artist to one who had at least developed the ability to put together a good comic book. I wasn’t really looking at what Mike Nasser, who I was at the time, was like as an artist. I was still in the state of the learning curve.

Batman (1940) #480, cover by Mike Netzer.

Certainly, by that time there was a turning point where we had went from the amateur/rookie that was groping around in the dark for something to hold onto to, “See, here’s a guy who can do professional comics.” It was an interesting change. There was a lot of criticism, still, of my work. Because it was so much like Neal’s. But it really didn’t bother me. I had such admiration for Neal’s work that when it would come up that, “Well, you’re a Neal Adams clone,” well, if I’m going to be a clone, then I’m happy to be the clone of one of the better artists out there.

It seemed to be enough for me at that time. It was that second year that things started changing. I had a personal situation that wasn’t very easy going on in Detroit and then her mother, who I couldn’t bring to New York when I was making $30.00 or $40.00 a page at the time and sometimes a page would take a couple of days to do and living in New York was a very expensive thing. I was sharing an apartment with people who were young artists who were still looking to get work. Whatever money I was making at the time sometimes had to be shared with the people you’re working with. Sometimes someone would want to go out to eat or something and because not everybody is working so whatever money was being made was going out more quickly than it was being made.

I worked very hard to make a living in comics at that time. Especially when living in a community type of thing. So, there was a bit of a change happening in that second year, slowly building up. “You know, there’s something about this that isn’t working.” It made me invest a lot more time in working, trying to develop the craft more and more and more and there was an improvement. You could see from issue to issue that I was investing more time than I did on the issue before. It was improving and I was getting a lot of commercial work with Neal, doing illustrations for magazines, like a nice little illustration of Bjorn Borg, the tennis player that showed an ability to do a painted type of work, which was a very good piece. I had a good name, I had a good reputation, but something just wasn’t really working.

I needed to see where it was going. I couldn’t see myself forging a career in this particular direction that things were heading into. The business was not compensating enough for the work needed in order to do really good work. Neal at Continuity, had a whole different reality. He was into commercial art long before he came into comics. He had an infrastructure. He wasn’t doing that much comic book work. The little bit of comic book work he was doing at the time was really supplemental to a large amount of commercial work, so he never really had that problem.

Amazing Spider-Man (1963) #228, cover penciled by Mike Nasser & inked by Joe Rubinstein.

For me it was like I was still young. I was coming into my own. I became aware that this was a time in life when you had to decide what you wanted to do. Who you are and what you’re going to do with your life? I had some friends who were very uptight at the time. It was very interesting. They would say things like, “This work is so good, but why are you doing comic books?” I would say, “Well, what else would I do? What else can I do? I’ve been drawing illustrations.”

Certainly, today in hindsight that wouldn’t have been a very good choice because the illustration work was all being done in the commercial art market the way it was in the 70’s was totally different. You had commercial artists doing movie posters and magazine illustrations…you don’t see that any more. Or at least very little of it.

Stroud: Right. It’s all gone to photography.

Netzer: Exactly. On the other hand, and I think this is what creates the turning point, there was a world of comic book fandom that we were part of which was a very interesting situation. We would go to these conventions, whether in New York or New Jersey and we were invited to these conventions in Detroit and so on and we would go like celebrities, like stars. They’d pay your way, give you a motel room and you’d get to the place and you could do sketches and make a few hundred dollars doing that and at the convention you could sell original art. The reception from fandom was phenomenal! I mean you go to a convention and you sit on a panel with a few hundred people in the audience and you could talk about anything you wanted to and it seemed like the audience were completely fascinated. “Tell us what you’re doing. Tell us about the comic book world. Tell us about these characters. Tell us about this, tell us about that.”

This was an interesting phenomenon, and to me it seemed to be more important than anything else that was happening around me. It was like this wonderland and anything that was happening in my life was this cycle and to me that was very important.

Now the thing about it is that whatever the problems were at the comic book industry personally at the time, they weren’t just problems of the industry itself. The industry is part of a larger, financial wheel that the whole world was in at the time. There was a course that the world was taking at the time, it seemed to me, that was not portending good news for the long road ahead. Further ahead in the future. It seemed at the time pretty clear to me that things were going to get worse and not get better. It seemed like, from the little experience that I had, from working those two years, that the direction was that financially, for people like us, it was going to get harder and harder as we moved along. Not just for us, it seemed like for everybody in the world.

House of Mystery (1958) #276 pg.12, art by Mike Nasser.

The world was heading on a course where the strong were going to get a lot stronger and the weak are going to get weaker. It’s just the nature of things. And certainly, looking back on it today 35 years later, it has borne out to be a fact. You could say that life is better for some people, but I think generally that the general picture is that life has become harder for almost everybody. And if you are succeeding and are able to find your place, then you can count yourself among some of the lucky ones, but that generally isn’t true for everybody. It certainly isn’t a situation where you could say that the general quality of life is getting better for everybody.

It’s like the myth of capitalism. The myth of capitalism was that everybody has an opportunity. Well, it’s true that everybody has an opportunity, but everybody can’t succeed. They might try very hard, but it takes a lot of things for someone to succeed. The savvy to be able to be a good businessman, which sometimes means that you have to be pretty tough with people and take things by force and do things in your position and stature in order to basically get something from someone that you couldn’t get otherwise. And what if you’re not that materialistic sort of guy? If you’re an artist, sometimes you’re just interested in the craft. “I want to tell stories. I want to draw well. This is what I love doing.” Well, that’s like a whole different reality from someone who is a savvy businessman and is going to succeed.

I mean, come on. You have guys like Mike Kaluta and Bernie Wrightston out there. Where are they? Why aren’t they working? Why aren’t they doing projects? The popular interest in artists and writers in comic book properties is like with DC and Marvel where we discussed that “We will decide what’s going to be popular and what isn’t. We make the distribution decisions and we do this and we do that.” It’s to the point where talent like Jeffrey Catherine Jones, who is one of the most phenomenal artists who probably exist on the face of the earth today, is relegated to doing commissions. Like an unemployed artist. He’s doing commissioned artwork for collectors because there aren’t any jobs in the industry based on who gets picked and chosen. It’s a really wild situation if you think about it. The great artists of our generation, of that time period, basically have no place to work today. And I’m not just talking about them, I’m talking about the regular people like Bob McLeod and George Harras and everybody who were important to the industry at that time. Today it’s like they’re on the margins and have to fight for any one particular job, and it remains that way.

The Defenders (1972) #87, cover penciled by Mike Nasser & inked by Al Milgrom.

I believe that at the time I had a feeling that this is how things would go and it’s going to take something very serious and big to be able to affect any kind of change. I think around the time of my second year up there that I sank into this state of repositioning myself. And maybe in a search for myself; who I am, what I am, what am I going to do with my life; in order to come out of it in such a way that I can find a direction that would offer something a little better than the one that was being offered to me at the time.

I suppose you’ve heard stories about that particular period. Basically, what I’ve given you up to now is a bit of the important background to explain the necessity I felt for some kind of change.

Now, the change that I was going through at the time…and I remember many times being out with Howard Chaykin and Gray Morrow sitting and having a drink downstairs and I remember Howard saying, “Mike has really become quiet. He seems to be not engaged in anything any more.” This was in the later summer of 1977, and I really was at a point of change. I was still at Continuity and I kind of disengaged myself totally from everything that was going on. I was still doing some work, on a big collaboration story and it was done and I was at sort of a standstill. I had friends at Continuity, the younger crowd who pretty much felt maybe the way I did, although they were still chugging along trying to find themselves and get a footing in the industry.

At some point I came to some conclusion that this wasn’t working and I needed to change. I just wasn’t sure where. But I did start asking myself, “What do you want to do?” I think that from that position that I was in, instead of going in the direction of, “Well, why don’t you take care of yourself, maybe go find some other career and see if you can go somewhere else, maybe leave New York and go back to Detroit and see if you can set up a home for a family, try to keep the family back there together,” instead of doing that, I did another thing. I said, “I want to see what I can do to change things.” I know it’s a big thing that you can’t really change. Look at the economy; look at government; look at the world infrastructure, which everything in your environment is connected to; which everything in your local environment is influenced by. This is the beast that you have to deal with. This is the world that you’re dealing with and if you want to change something you have to deal with the whole thing in order to influence your local environment. And unless you can have some kind of effect on the whole package, you’re not going to be able to change anything.

The Comet (1991) #12, cover penciled by Mike Netzer & inked by John Beatty.

At that point, for me, it was like I had nothing to lose. I simply had nothing to lose, so at that point, when you’re going into this spiritual thing and you’re asking yourself, “What do you believe in?” It brought me to a place saying, “Well, I’m the kind of guy who looks at history and where humanity is today and I look at all of the influences that have historically had their impacts on civilization.” I realized there are a lot of factors that need to be touched on in order to have an influence on what’s going on in the world. Some of them being religious, some of them being spiritual, some of them being economic, some of them political…but there were a lot of things.

I think that I took it upon myself to be some kind of person who would at least step aside form this thing and see what you could do and at least find out who you are. For me, at the time, when I think of it, of what drove me into this particular corner, I would say that I certainly had an idea of history. I thought that historically, the kind of local world we live in wasn’t always in tune or in touch with the larger picture of how humanity has evolved to become what it is.

Let me give you an idea: Here we are, a group of comic book creators, working in an industry like underdogs, being taken advantage of. We can’t get our shit together enough to put together a union or a guild, and yet the same creators who are not able to create this one simple stand as a group of people, these are the creators that are sitting down and writing and drawing stories of the greatest heroism that humanity can imagine: The mythology of superheroes, which involves sacrifice, and of good fighting evil. It’s like we were able to write it, but we can’t live it. We are powerless. It seemed like a big dichotomy. Even a hypocrisy, I would say, to sit and write these stories but we’re not able to do the slightest kind of thing to improve our lot in this life.

Stroud: Ah-h-h-h.

Netzer: Ah-ha! So, I was starting to see my environment and saying, “Guys, what are we doing here?” It started becoming like meaningless. It seemed to me that you have to show, throughout your whole life, that we need that same thing that we’re writing about in the comics. We needed to because the world needs it. Because we need it. Because our children will need it. Because the way things are going, it’s going to get worse and worse. And there doesn’t seem to be anybody that is making a real stand. If it was Neal, then he was a lone soldier. There were a few. But Neal certainly didn’t seem to have the support of the industry. If the comic book creators had come together to help create this guild, then they would have. But their fear for their particular state prevented them from doing the heroic thing that needed to be done. The very same thing they were writing about in the comics all the time! They were writing about it! They were writing stories about sacrifice and fighting evil and it was just, “We were writing about it, but I’m sorry, we can’t do it. I don’t want to jeopardize my income here.”

Kobra (1976) #6, cover penciled by Mike Nasser & inked by Joe Rubinstein.

Stroud: Quite the contrast.

Netzer: So, to me a lot of this took a rather…let me tell you this story. As a kid, I remember being 4 years old and I was in Lebanon. In Lebanon, just like in America, just like in every other culture, a kid growing up, one of the things he hears, that I heard at least, which made a big impression on me…just imagine yourself as a kid: Everything is new in the world and somebody says, “The painter is coming to paint your house.” And you see the guy coming to paint your house and you know what that is. And if someone says “painter,” you see that he paints houses and then you ask an adult, “What does that painter do?” That is the most simple, basic curiosity: To learn new things, and as a kid that’s what it is: A series of learning one new thing after another.

So back at the age of 4 I remember hearing all the time people saying, “God forbid, God willing,” this whole thing where God is all the time coming out of people’s mouths. I remember asking an adult one day at 4 years old, sitting on the steps of the house, “Where is this God?” It seemed like this must be a big guy that everyone had this reverence for, and I was wondering who he was. “What are they talking about? Who is this guy?” I had this impression about him, but he never came around. I never did see him. So the guy looks up and he points at the sun and says, “You see that? On the other side of that, he’s over there.” It kind of drove me crazy at the time. “Really? Come on, I’m not stupid. I know that you don’t mean it, right?” You’re talking about something that you believe in, and yet you really don’t know what it is. I was really enamored with the subject. And it was on a slow burner. As a kid growing up, I would conceive of these stories. I was into science fiction, and I was into the superheroes, and it seemed like all of the stories I tried to put together and write, whether I was doing samples, or whether I was looking ahead at a time when I would become a comic book artist, a lot of them involved some kind of future that put forth the idea of discovering the Creator and what he was.

It seemed that this was all good and fine for a child, but at this particular point in my life that we’re talking about, my second year of comic books, I began to think, “Well you know, Mike, you could take it upon yourself to go out and try to change the world; the way things are, but you know this sounds like a really big (something.) It would be good for you to include that in all the periphery of options that you are considering. Whatever it is that you decided to do.”

Marvel Team-Up (1972) #101, cover by Mike Nasser.

It reached a point where I was sitting with this girl in New York, a friend, and she asked me, “What are you going to do now? You’re not finding yourself in the comics.” I said, “I don’t know. I wish I could use my talents in the industry to say something to the world.” She said, “What would you say?” I remember writing down, “We should love each other.” This seemed to me to be a very important message. She said, “Okay, so what? Where do you want to take this?” It seemed to me this was a very big message, and then the connection came: This really is the core. I’m not talking about religion. Surely religion hasn’t really fomented that message. But the source of religion does. And I thought that I would want to go and figure that out. To see what it was that source was talking about.

So at some point I put myself in that position, and at one point I said, “This is going to be the next step.” Then I made the decision to leave New York and to go spend some time in the mountains and on the beaches of California. Just to clean up inside. To disengage from the hustle and bustle of what was going on in New York and to clear out my mind. It seemed there was something in all that that I could grab. So I did that.

One day, it was the 19th of November, exactly three years after I went to Continuity, and after two years of a very intense comic book career, I met somebody early in the morning at Continuity and I said, “Tell everybody I’ll be gone for a month or a month and a half and don’t worry about it. I’ll be back.” And that’s what I did. I had ten dollars in my pocket and went out on the George Washington Bridge and hitchhiked out to California.

Stroud: Wow!

Netzer: In search of whatever it was I needed to find. I won’t go into every little thing that I learned, but the bottom line is I arrived in San Francisco exactly 7 days later. It was Thanksgiving Eve. I’m traveling by hitchhiking. I have nothing on me. I’m living from day to day and moment to moment in whatever it is I run into along the way. I’m surviving, though the ten dollars was gone the first day. I was having this experience where I was going to see that if you believe God is with you on this thing, let’s put it to the test. We’ll see if he’s still there on the road. And it did in terms of being afraid. I mean if you’re going to go hitchhiking with nothing on you, what are you going to eat? Where are you going to sleep? And yet everything along the way seemed to take care of itself. I never was in need of anything.

Challengers of the Unknown (1958) #82, cover penciled by Mike Nasser & inked by Joe Rubinstein.

I arrived in San Francisco and there was a Thanksgiving dinner there being given to those who were homeless and so on, so I joined them and had a nice Thanksgiving dinner. Then I walked out of the place and I see this ad pasted on some glass looking for an illustrator with a phone number. Now interestingly enough, Mike Friedrich at Star*Reach had contacted me and wanted me to do the first 8 pages for that magazine. I was starting to do it, and I never got around to doing it, and when I saw this name I thought, “Oh, my God. He needs that job in another couple of weeks,” so I called Steve and said, “Steve, this is Mike and I’m here in San Francisco. I’m not going to be able to finish that job and you can tell Mike I’m really sorry.” He said, “What are you doing in San Francisco? Come on up here and we’ll talk about it. Mike won’t want to let you go.”

So, I make my way to Steve and he calls Mike Friedrich and Mike comes by and asks me what I’m going to do. “I can’t do comics any more.” “Well what are you going to do?” “I don’t’ know. Maybe I’ll go around the country and talk about bringing about world peace.” I was in a frame of mind for setting things up for a larger situation. He said, “Well, the story you were going to work on wasn’t really regular science fiction, it was just a special thing, but maybe you could write down what you’re going through and we could do a special feature.” So that’s what I did. Basically, I stayed with Steve for a couple of days and that’s what I produced. That 8-page story that was in Star*Reach. I don’t know if you’ve seen it.

Stroud: I have not.

Netzer: It’s got three parts and in “The Final Testament,” it basically represents our coming to the point that we’re colonizing another planet. I was looking at our religious history as a catapult to our future and that’s the last chapter of our history, like spiritually. It’s basically being applied toward a continuation of humanity, colonizing in outer space on another planet. I specified Titan, the moon of Saturn. I don’t know where that came from at the time. There was just a feeling about Titan because I’d read a lot of books about Titan and there was this thing in mythology about Titan being very earth-like. I really knew very little about it, but I needed somewhere, so I set that up as the target.

So, I left it at that. I was in such a state at the time that I really didn’t understand it. Any effect that it would have. But as strange as it was, Mike Friedrich thought that it was worth publishing. At that particular time and place it seemed like a good thing. The message was a positive one, so he published it and he wrote an editorial about what I was going through and I think it contributed a lot to a big story that was starting to form about what had happened with my leaving Continuity and I came and saw him and I’m studying religion and I still had no idea where this was going.

The Defenders (1972) #88, cover penciled by Mike Nasser & inked by Armando Gil.

So I left Steve and Mike and went out to Southern California to San Clemente and spent a lot of time on the beaches and in the mountains and I met people here and there and I took a Bible from somewhere and I read it through four times. I just wanted to know it. I’d never read it through completely and I wanted to know all that history. I wanted to know what was in the book. There certainly was grandeur in the stories. I’m not talking in a religious sense. I’m talking as stories. In the sense of what the people did. The prophets and what they did and that was the sort of force that we needed today. It seemed to me that this was what was needed in the infrastructure to face what was bringing civilization down. The main reason for it was to encourage. To bring out the spirit of hope and goodness in humanity. This was what it was all about. Everything that was missing from the jargon of modern civilization. Not necessarily in the sense of religion, but of what’s right. There are people that need help here. There are people that have a lot of power and a lot of money and then there are the people that are starving and dying and it seems that the powerful are only engaged in getting more power for themselves and engaging in activities that are only distracting everybody and not being able to face the evil that is standing in front of us. That connected to me.

It took a long time to be able to put that into perspective. Maybe 20 or 30 years. But I really didn’t have a choice at the time. I was already into it. I had stepped into the cold water and I found myself in the mountains of California, walking around, living outside, living with whatever nature had out there and reading this book and absorbing it. And what did I find in it? Well, I found a lot of things, but very interestingly I found it in both the Old and New Testament that they had a common thread that touched me. In the book of Daniel, it mentions the name Michael in this very strange context; like at times, Michael will stand up. Looking at this verse and at the whole thing that preceded it, I had no idea what it was about. There were things about the kingdom of the north and the kingdom of the south, but it turns out to be a very important prophecy and there’s this name. Somebody is going to come in time and they have this name and I thought, “What is this? Is this a set up?” Then I continue reading through the New Testament and you get to Revelation and there you see the name being used again! “They will rule all nations with a rod of iron and there was one in heaven, Michael and his angels,” and I really didn’t put the two together, but coming back again in a similar context and I found the name and thought, “All right. I’ll do it.”

Peter Parker, the Spectacular Spider-Man (1976) #37, cover penciled by Mike Nasser & inked by Joe Rubinstein.

So, I came back to New York, feeling new and invigorated and being sent from God kind of thing and I arrive at Continuity and everybody is looking at me kind of strangely. Neal said, “Mike, you have religion!” He’s laughing it up and I’m really serious. This isn’t some kind of joke for me. I’m not a happy guy any more. I’m not that kind of person any more. I’m very serious. I don’t know what’s going on here, I’m just walking into the lion’s den and I have no idea what’s going on. So, I just shut up, go back to my room and sit with Marshall Rogers and ask to be left alone.

So, I went back to the room and suddenly there was tension. That night I’m sitting with Joe Barney and it’s 3 or 4 in the morning and Joe Barney is one of the artists who work at Continuity and there’s this radio talk show from one of the New York stations and they’re talking about Steve Ditko. It was a show that talks about comic books and Joe Barney is trying to get a few words out of me. “What happened? What’s going on with you?” I still didn’t know how to put it into words and I said, “Look, Joe, do you see this?” I showed him Revelation, Chapter 12, and he says, “Mike, you know, that’s talking about the second coming of Christ. You’re not saying you’re the second coming of Christ?” I said, “Joe, I’m just saying, I went out there looking for something to do and I found this in the book. I don’t know.” He said, “Well, if you really believe it, why don’t you get on the radio and say it here? I’ll dial it.” So, he dials into the radio talk show, and I get on there and I said, “I’m Mike Nasser and I’m working at Continuity,” and they move me right up to the front. I didn’t have to wait very long. The guy comes on and suddenly I’m on the air and this guy says, “We have Mike Nasser, and he works at Continuity Studios, and he might have something to say about Steve Ditko. Hello, how are you? What’s on your mind tonight?” I said, “We’re putting together at Continuity a political party for the 1980 elections.” Then there’s a silence like, “Where did that come from?” I mean, I’m Mike Nasser, and I’m supposed to be talking about comics. He said, “That’s very interesting. I have a feeling there’s something else you want to say.” I said, “It was written that the second coming of Christ would be a man named Michael.” More silence. And the guy said, “Well, Mike, if you really believe it, then I wish you all the luck. Thank you very much for calling.”

So, it’s like 9:00 and Neal comes bursting into the studio, “Was that your voice I just heard on the radio?” I said, “Neal, I was just answering his questions.” I felt I was placed into this position by one event after another. I can’t even begin to tell you what the beginning of this thing was, but certainly up until Joe Barney said that word, I had no idea that the use of it was intended. And yet I went into this with open arms and an attitude of whatever happens, happens. Suddenly it started becoming bigger than life. I was hearing, “Mike, this is Continuity Studios. We do comic books. We don’t make political parties here, and we certainly aren’t running any kind of movies here, so this isn’t going to be easy for you.”

Uri-On (1987) #1, cover by Mike Netzer.

So basically, what you have is this thing developing, with 20 or 30 people always visible in the studio and everybody has their own feelings and they just don’t talk about this thing. I mean Continuity really isn’t the kind of place for a born-again, religious type of thing. It’s not a church. That wasn’t what I had in mind, certainly. I was thinking, just take it a step at a time and see where it goes.

So, I went to a convention a couple of days later and somebody took a picture of me, with my beard and they published that in the next Comic Buyer’s Guide and some of the magazines and they published a few articles and the picture and it said, “Mike Nasser,” with just the photo and nothing under it. Usually there would be something about the guy. “We saw Michael here,” or something. Instead it was just the photo and why? Because there was a buzz. It was about Mike having gone crazy and coming back with this religious thing and him thinking he’s the second coming of Christ and now it was a matter of how do we deal with that? Then it was a matter of somebody saying, “Look, you can’t do that and you’ve got to go.” This was Mike Nasser, who had become a big, promising talent in the comic book industry and it just wasn’t going to be that easy.

The thing is, Neal, interestingly enough, caught on right away. Now if you think of everything we talked about before, it’s very interesting that Neal, who might not give away what he believes in religiously or not, though he has a couple of times; and I would only say that there was an interview he did with Silver Bullet Comic Books a few years ago called “Neal Adams, Renaissance Man.” If you search for it, you’ll see a 5-part interview with him and he makes this interesting statement, and this is probably one of the few instances where we see what Neal thinks of the subject. So, what does he say there? It’s interesting that this happened at a time when my there was some talk about Mike coming back from this Messianic trip and here it is 30 years later and Neal is being interviewed and when asked about religion he said, “You know, I think there’s a lot of truth in religion. But I think there’s also a lot of lies. And I think one of the reasons I like talking about growing earth and science is maybe because people are uncomfortable talking about religion. Maybe people will be more comfortable talking about science and maybe one day they’ll be comfortable talking about religion. They might want to stone me to death one day for saying the things that I say, but I think one day that it will need to be said.”

Uri-On (1987) #1 pg.1, art by Mike Netzer.

I read that and I’m thinking, “Gee. I’ve never heard Neal talk about that.” I know Neal. So, what happened was, back then, Neal understood exactly where I was coming from. He used to say, “Mike, you’re a fluke. What’s a fluke about you? The fluke about you is that you’re this guy who is like looking at the big picture of things and you have this long-range vision of where you see your name in the book and you want to take on that role, and you’re in a position where you can effect something.” It was like the comic industry in the 70’s. Everybody else didn’t understand how big the comics industry would get, but we understood. Neal and I certainly did. We knew that the comics industry would become a very pertinent part of the culture in the world. Everything that was happening in the comic book industry would eventually have an impact in the world. He thought that at the time, just like I did. This was exactly where I was coming from. And we’re not talking small potatoes any more. We’re talking about the kind of thing that says, “Well, we’ve got comics fandom. We’ve got a lot of people and we have to open up the subject.”

The end point is to present this kind of a figure, that maybe it’s worth it to be able to change something in this world. He understood me, exactly the way I’m saying it. And he supported me. A lot of other people thought, “Well, Mike is just going through this religious thing.” Nobody else understood. I remember him coming back to my room a few days later while all this was happening. I did this 8-page story for Hot Stuff magazine which had this spiritual intonation to it. Not necessarily religious, but certainly spiritual, and I remember him coming back there and saying, “Mike, you can’t just sit there, you have to do something with comic books. Use them as your wheels.” It was like he was egging me on to get off my butt and do something, draw something, look for work instead of just sitting there and acting like some sort of prima donna and acting like I didn’t need to make a living like everyone else. Which is what I was doing at the time, because I really had no idea what it is I needed to do.

Shazam (1973) #35, cover by Mike Nasser.

So, he comes back and he says that and Larry Hama comes back and he says, “Neal, why are you encouraging him like this?” Neal turns to him, kind of flabbergasted, and he says, “You know what, Larry? One day, Mike’s trip to California is going to become the basis of a new religion,” and I thought to myself, “My God, Neal, what the hell are you talking about? That’s not what I’m talking about. I don’t want a religion. I think most religions are pretty bad as far as what religions have done to the institutions of the world. It’s not been a very positive thing.” I mean, the most positive thing you can say about religion is that they have preserved the writings of great stories that have an influence on the common people. But the average religious person I don’t think would come out and do the things that they’re supposed to do. I don’t see anything in the Bible that says set up a religion. I don’t see Jesus saying to establish Christianity. I don’t see Moses saying, “Become religious.” Not at all. I see stories about righteousness; about justice. I see stories about people having a personal relationship with their faith. But I don’t see a call in the writings to establish a religious institution. I don’t see the writings calling for worship of the institutional type that religion has become. Then you look through the history and you realize it’s true.

Just think about the story of Jesus. Just as an aside. He comes, and he’s not into worship. He goes out and basically spends a few years on the road talking to people and eliciting popular support for a movement that stands up to religious hypocrisy. By teaching what the actual meaning of the scriptures are. And his biggest enemies are the religious people. The people who basically come together to run to Pilate to put him to death are the religious people. Much of it run by the high priests. So this is how religions were developed. A prophet comes along, goes out on the street, brings the voice of the people against the establishment, writes the story down, the writings later become the basis for a new, specialized religion, that basically at some point will need another prophet to come and stand against them. That’s religious history. It’s not about the spiritual. The only thing that the church has done or the synagogue or any institution, basically, is preserve the writing. But it seems that the writing would have preserved the stories anyway. Or at least what we could expect from religious institutions, what we could expect is to receive the message of the writing. And the message of the writings do not ask for this kind of separatism. Or this kind of pride in being; a religious pride that creates an animosity between you and those who choose not to be religious. The writings don’t ask for that. That’s what religious institutions do.

The Defenders (1972) #89, cover penciled by Mike Nasser & inked by Joe Rubinstein.

So, the question is, why is all this important to a comic book artist working in New York at Continuity in the mid-70’s? (Mutual laughter.) I don’t have an answer for that, but what I do know is that I went in this direction and I found a big world that was like finding my way a little closer to the truth about all this and what do I find? I find resistance. I find people back here saying I can’t say that, I find other people saying I can’t say that. I get, “Oh, Michael, you can’t talk that way about that.” What I’m talking about is really a lot more truth in the original writings and the spirit of the stories that came out of the writings that the world seems to be ruining in many ways. I mean look at what’s happening in America today.

The political conflict in the world today, the political dichotomy, it seems that the powers that be today are very happy that people are at each other’s throats. You’ve got the Right and the Left and the Liberal and the Conservative and they’re all at each other’s throats and the powers that be are happy because we can just forget paying attention to how they’re just running our world into the shit heap. Humanity is basically being subjugated and the economic structure is such that we’re being left powerless to do anything in the way of good in the world any more.

Now on the humane level, people have the choice to do good and to help make their environment better and they do. The only thing is that we’re working against really tough odds. Because the general spirit of things and the good that we try to do, we’re doing it against overwhelming odds against a very big, strong infrastructure which is not really interested in the well-being of everybody. It seems to be more interested in its own well-being and power and subjugating everybody.

So, at that age and that position I took all that on and basically one thing was clear to Neal and to myself. I’m saying if I’m going to see this through, and he would be there, I knew that he would, he would be there to be a part of it, I know, I’ve been in touch with him enough to know, that we basically understand each other. We have this history, which has not always been on the best of terms. We went through this thing in the 90’s with the lawsuit and there might be some blood between us, but still, both of us, I think, understand that as far as the big picture is concerned, nothing has changed. What he did back then at Continuity after that period of my going and coming back and making that first stand and trying to change the spirit of things in the studio at least to try and set up for some kind of creation of something that would go beyond talking about the superhero and trying to do something of some heroic value in the world, it was clear to me and Neal that it was like it would have to step out of the comics periphery.

Challengers of the Unknown (1958) #81, cover penciled by Mike Nasser & inked by Neal Adams.

I think that it was inevitable that I would not be able to keep working at Continuity. I think Neal understood it, too. Interestingly enough, if Neal had not pushed when he did, he pushed me not to forget, “This is what you took on. This is what you said you were going to do.” I remember at that point, after I’d come back from California, that first day, I had my room and Neal was trying to bring me down to earth as far as having this big Bible in the front room and he was reading it all the time and he was arguing with me about not looking at things in the religious sense, but in a spiritual sense, but he was doing it through the Bible. He was showing me verses that had to do with work and it had nothing to do with worship and he basically understood exactly what I was going through and he was trying to guide it into a particular framework that would be practical in a way that we both thought would have an influence on the industry and on the world.

In that sense, he pushed me into this thing. I might have, if it wasn’t for that, those first couple of years from about ’77 to ’81 when I left New York for Israel, if it wasn’t for his particular pushing, I might have said, “All right, guys, I just went through this thing and I’m sorry, I’m back to doing comics.” I might have done that. But Neal wouldn’t let it happen. So, I found myself back to like before. There’s this harmony between us. He was saying things one way and I was pushing more in another direction and it’s very hard to explain now, but I remember one issue. I did the Batman Spectacular at the time, which was the one with Marshall Rogers and Michael Golden which was a Superstar Spectacular, a DC Special, and that one story, which was one of my better stories, which was in early 1978 and after it was done it was like my roommate, John Fuller, said, “Come on, let’s go. Why don’t you come back to California? It doesn’t look like you have many friends here,” and that kind of thing. So, I said, “That’s a good idea. That fits into my plans. I need to be outside a little more.” So, I went to California. I drove across the country and spent some time in California. But the thing with Neal was like he was representing this position as to where he thought this thing should be and it was if he was challenging me. “Mike, if you think what you think; if you believe what you say here, then you have to be able to present yourself…” He was challenging me, and I can’t put it any other way, so while I was in California, all this was running through my mind and he kept asking, “Are you going to be able to answer all these important things about this history and when I got the answers together I thought, “Well, it’s time to go back to New York.” So, I got back to New York and I did this 11-page story, which wasn’t really a comic book story, but it was in comic book form and it was from what I’d done during that period.

Secrets of Haunted House (1975) #24 pg.20, penciled by Mike Nasser & inked by Vince Colletta.