An Interview With Ramona Fradon - The Woman Who Co-Created Metamorpho & Aqualad

/Written by Bryan Stroud

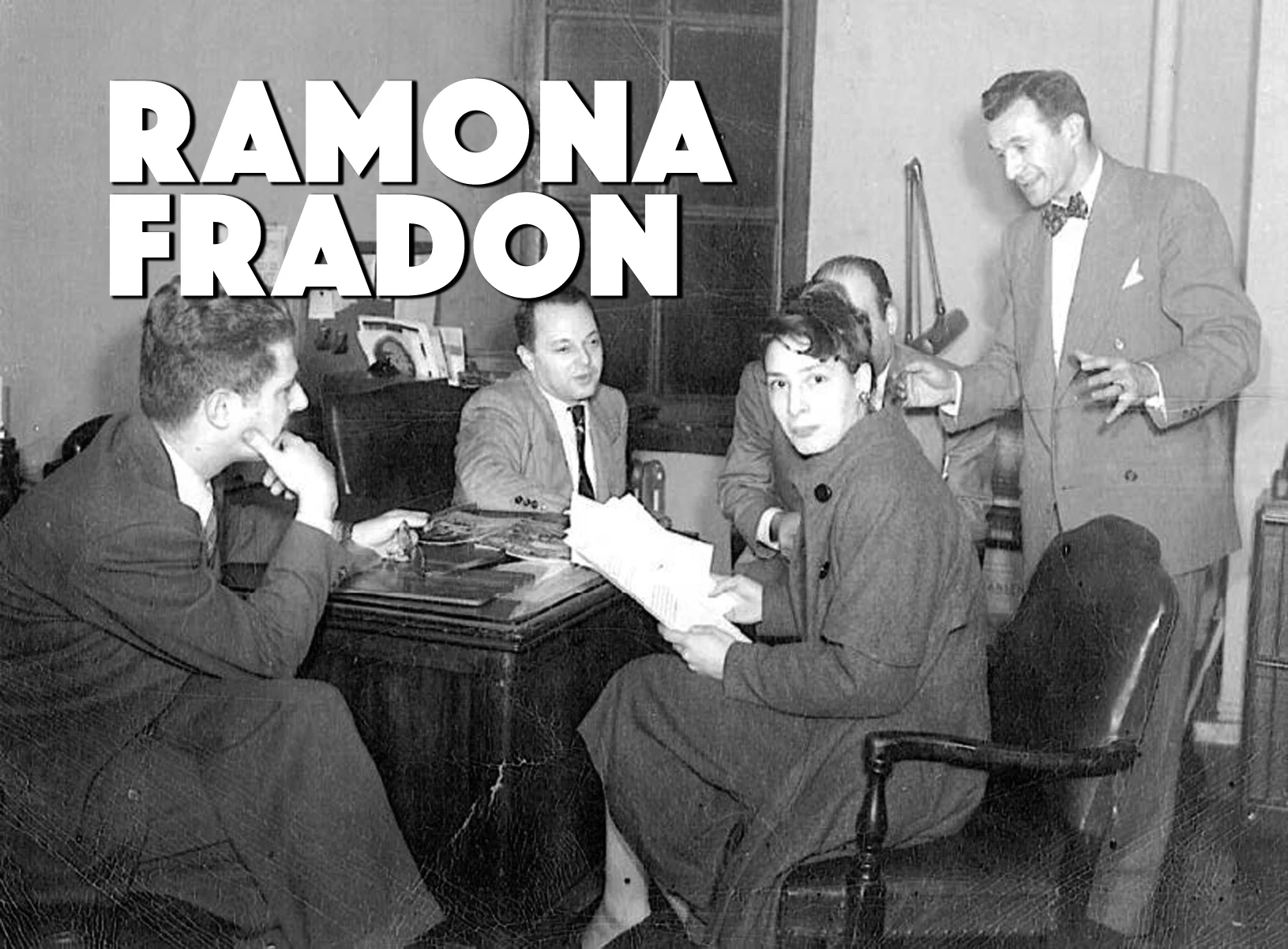

Ramona Fradon sitting in a bullpen, surrounded by male co-workers.

The Silver Age of DC comics contained everything from the sublime to the ridiculous and sometimes you had features that sort of straddled that line. I've always been fond of Metamorpho, the Element Man, so it was a natural thing to reach out to his original artist, the wonderful Ramona Fradon. Since that first e-mail interview, she's helped me with a couple of articles I've done for Back Issue magazine, both on Metamorpho and Plastic Man. In 2015 I had the great good fortune to meet her and purchase one of her pencil sketches of Rex, Java and Sapphire in San Diego. What a treat it was!

This interview originally took place via email on June 12, 2007.

Bryan Stroud: According to some information I found, you began at DC in 1951. The industry was pretty much on the ropes at that point. What prompted you to try comics at that particular time?

Ramona Fradon: I didn't know anything about comics at the time and didn't know if the industry was on the ropes or not. You might say my husband and I were on the ropes financially, having just gotten out of art school and living on 75 dollars a month from the GI bill. A friend of ours, George Ward, who was later Walt Kelly's assistant, urged me to make some samples and take them around to the comic book companies, which I did.

Stroud: What was your first job at DC?

RF: It was a four page Shining Knight.

Stroud: Did you have aims to be a comic book artist?

RF: No. I had read the newspaper strips when I was a child, but had never read comic books and had never thought of being a cartoonist. I married one, however, and that had an influence on me.

Metamorpho (Rex), Saphire, & Java by Ramona Fradon.

Batman by Ramona Fradon.

Catwoman by Ramona Fradon.

Stroud: Gaspar Saladino began his career in the fashion industry. Is your background similar?

RF: No. I came right out of the Art Students' League in New York having studied fine art. My father wanted me to be an artist so I went to art school, but had no idea what I wanted to do after that. I was lucky to fall into comics, I guess.

Stroud: How many other women were working as comic artists when you broke in?

RF: As far as I know, only Marie Severin at Marvel.

Stroud: Was there any resistance to your penciling super heroes?

RF: The only resistance was on my part. I always hated drawing superheroes and the editors kept assigning them to me. I preferred drawing the mysteries and goofy characters like Plastic Man and Metamorpho.

House Of Mystery #232. Cover by Ramona Fradon.

House Of Mystery #273 interior page by Ramona Fradon.

The Brave And The Bold #58. Cover By Ramona Fradon.

Stroud: Did Bob Haney have a specific look for Metamorpho in mind or was the design left up to you?

RF: I did a number of sketches before I arrived at Metamorpho's look. Bob and George Kashdan both approved it.

Stroud: Why did they use the Brave and the Bold title for Metamorpho’s try-out instead of Showcase?

RF: I have no idea.

Stroud: A house ad in the summer of 1966 stated that Metamorpho and Wonder Woman would be appearing in the fall on television in “Colorful Animation,” but it never came to pass. Do you know why?

RF: No. I knew at the time that someone was interested in doing a cartoon of Metamorpho, but I stopped drawing it and lost touch with what was happening.

Stroud: Have you seen Metamorpho’s animated debut on the Justice League series recently?

RF: Somebody sent me a video of an episode, but I must confess, I haven't looked at it yet.

Showcase (1956) #30 pg1, art by Ramona Fradon.

'60s DC House Ad promising "Colorful Animation".

Showcase (1956) #30 pg6, art by Ramona Fradon.

Stroud: Why was your run on Metamorpho cut short? Do you think his magazine’s early demise was influenced by the change in artists?

RF: I only agreed to get it started. I had a two year old daughter and wanted to get away from deadlines and be a full time mom.

I suspect that it was. Bob Haney and I had a synergy when we were working on that feature, and I don't think it had the same energetic core or humor after I left

Stroud: Sapphire Stagg was sort of a cheesecake character and she and Rex Mason did something unusual for the day, which was to publicly show affection. Whose idea was that? Was there any flack about it?

RF: Bob Haney wrote the scripts and it was his idea. But even more unusual was having a freaky looking character like Metamorpho be a romantic hero. But that was the sixties, and what can I say?

Stroud: What sort of model did you use when you designed Java?

RF: I had my big brother in mind who was a kind of caveman type. He used to torture me when we were kids and I got back at him by drawing Java. I never told him, of course.

Stroud: Did the fact that Rex Mason didn’t want to be a hero influence how you handled the character?

RF: Rex's dialogue and actions spoke for themselves and influenced the way he looked

Metamorpho, The Element Man #2. Cover by Ramona Fradon.

Metamorpho, The Element Man #2 original cover art by Ramona Fradon.

Metamorpho, The Element Man #2. Cover by Ramona Fradon.

Stroud: Did you prefer covers to interiors?

RF: I didn't like doing covers, especially since I had to produce sketches on the spot for George's approval and I couldn't think under pressure

Stroud: Which editors did you work with? Were they easy to get along with?

RF: I worked with Murray Boltinoff, George Kashdan, Joe Orlando and Nelson Bridwell. Nelson was the only one who you might say was difficult. He was very exacting and protective of his story lines. He designed a lot of the characters and didn't want any deviation. I preferred inventing my own characters, but these were kind of mythological archetypes and I suppose they had to be what they were.

Stroud: Were deadlines pretty tight?

RF: They were only tight because I would wait until the last minute to do the drawing.

Stroud: Charles Paris inked a lot of your work. Did you like his style? What other inkers did you like?

RF: I liked what he did on Metamorpho. I think he contributed a lot of energy to the feature.

Metamorpho, The Element Man #2. Cover by Ramona Fradon.

Ramona Fradon

1st Issue Special #3. Cover by Ramona Fradon.

Stroud: What other pencilers did you like?

RF: At the time I wasn't aware of who was doing what. My favorite cartoonists are Eisner and Bruno Premiani.

Stroud: How was Bob Haney to work with?

RF: I enjoyed working with Bob enormously. His scripts influenced my drawing, and my drawing influenced him. We had such a rapport on that feature you might say we were walking around in each other's heads. .

Stroud: I can think of one magazine in the Silver Age you did outside the usual assignments; Brave and the Bold #59 with Batman and Green Lantern vs. The Time Commander. Was that a fill-in or were the editors trying you out on other characters?

RF: I don't know.

Stroud: Are you still active in the industry?

RF: I do an occasional story for publication and I do commissions and drawings for conventions.

The Super Friends #39. Cover by Ramona Fradon.

The Super Friends #41. Cover by Ramona Fradon.

Betty & Veronica #275 Ramona Fradon Variant Cover.

Stroud: What was the page rate at the time and did they pay you the same as your male counterparts?

RF: When I quit in 1980 to draw Brenda Starr, I think I was getting $75 a page

Stroud: Have you seen the modern version of Aquaman? What do you think? For that matter what do you think of modern comic books?

RF: Yes, I've seen it. Maybe the changes appeal to current readers, but he's not the simple, clean-cut Aquaman I knew. I suppose sooner or later he had to reflect on his situation, but why the beard, the hair and the hook? Maybe he's become delusional and identifies with Neptune?

Stroud: I spoke with Neal Adams earlier this week and he said he was a big fan of your work. Did you know that?

RF: No, I didn't. But I'm pleased to hear it.

Stroud: In later years you worked on the Super Friends and Plastic Man. Did you enjoy those assignments?

RF: See my answers to #6 and #16.

Ramona Fradon at NYCC 2010.

Ramona and the Super Friends - by Ramona Fradon.

Ramona Fradon holding a page of her original art.

Stroud: I understand you did work on the Sponge Bob Square Pants cartoon with the spoof Aquaman characters, Mermaid Man and Barnacle Boy. True? If so, what was that like?

RF: I loved it. The goofier the better. I just finished doing a Radioactive Man for Bongo and had great fun doing that, too.

Stroud: You’re still very active in the convention circuit. Are the fans receptive to your contributions?

RF: I go to San Diego almost every year and will probably go to the big New York show from now on. I also do others occasionally. Yes. I sell a lot of pencil sketches and enjoy meeting the fans.

Stroud: You still do commission work. How would someone contact you for a job?

RF: I can be reached by E-mail at ramonafradon@earthlink.net.

Gallery of Ramona Fradon Commissions

Wonder Woman by Ramona Fradon.

Aquaman group commission by Ramona Fradon.

The Riddler, The Penguin, and The Joker by Ramona Fradon.

The Demon by Ramona Fradon.

Hawkman group commission by Ramona Fradon.

Plastic Man by Ramona Fradon.

Super Friends group commission by Ramona Fradon.

Java, Metamorpho, and Sapphire by Ramona Fradon.

Green Arrow by Ramona Fradon.

Power Girl by Ramona Fradon.

The Spirit by Ramona Fradon.

The Justice Society of America by Ramona Fradon.